August 2, 2000

Baja, San Quintin

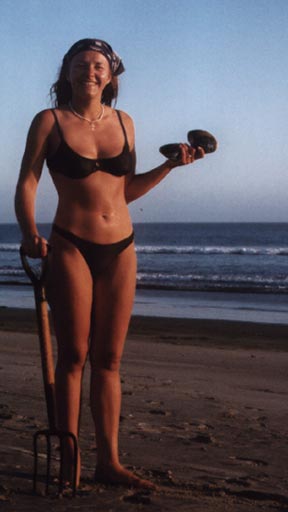

To the left is VANITY...

To the left is VANITY...

And her name is MARGARITA.

She's the reason I have very few pictures from a recent camping trip to Baja California, to San Quintin, except that she's in them. I planned to photograph the place, the people, the wildlife, the incredible Baja sea and landscape. But every time I went for the camera, there she was. She pleaded. She insisted. She demanded. She jumped up and ran to get in the way. She stamped her feet and got very, very angry. It's just that, from her perspective, any use of film other than on herself seemed an outrageous waste of time, money, and opportunity--her time, her money, her opportunity. She's working on a set of photo albums for when she's 80. So she can't stand the idea of missing a chance, any chance, to see then what she looked like right now, and right now, and right now, and right now. Beauty fades with each passing minute....

Margarita is my wife, so I'm in no position to argue. Besides, there's no arguing with Russian women once they're set. "No" is meaningless, just an empty sign of some vast, vague and entirely irrelevant male conspiracy against all things that really matter, especially personal vanity, its endless accoutrements and attendant privileges. And since she's also my venture capitalist, supporting me in whybother.org and other web adventures, who am I to say she can't have a page or two of flattering photos of herself? Believe me, just starting to post these photos is already making my life much easier.

Three of us took a week off and drove down to San Quintin on a whim...Margarita's whim, needless to say. Our friend Lucio (more recently "One must imagine Sisyphus happy" at My12Steps.com) had been traveling back and forth to Baja for some time, staying in various places and basically enjoying solitude, meditation, his books, and his writing. But as he was about to start another hermit stint, he made the mistake of hinting that Margarita might want to come along. She leapt for it, or maybe it was her hint in the first place. In any event, it would be a chance to realize her favorite English phrase since arriving in America nine years ago. "Let's go... let's go... let's go." Somehow I suspect that's her favorite phrase in any language.

Of course, there were complications. Lucio confessed he had second thoughts, half-wishing he hadn't offered to take Margarita, assuming he ever really did. There was simply no way that going down to Baja with Ms. Letsgo was going to be either simple or peaceful. But there was no backing out. And so I had to go, too, for full measure and to serve as a buffer between Lucio's dream of solitude and Margarita's urge to go on and on and on. Nice solution all around, but before we came up with it we made the mistake of trying to talk her out of going, telling her there'd be absolutely nothing to do where we were going, that Lucio just wanted to play hermit, that she'd be bored. Of course, she didn't believe any of it and got furious and hurt and furious again.

And in the end, she was right. She wasn't going to be bored. She had her own plans for all contingencies. If nothing else, we could always photograph her, for which purpose she packed almost no clothing except a swimsuit, jewelry, pearls, and her favorite blue dress--her idea of camping gear.

So we went, the three of us in a Toyota Tercel packed beyond its limits. It was my first venture into Baja, despite having lived on the border for almost eight years and hearing endless stories of the place from everyone all around. My reluctance has been largely a matter of political sensibility. It's not a question of feeling like a typical ugly American tourist. The three of us traveling together were hardly typical. Getting visas and crossing the border either way was hysterically cosmopolitan, what with a Nicaraguan, a Russian, and an American with a Cuban-Basque first and last name cramped in the same little Japanese car.

My reluctance arises from having to confront directly not only the symbols but the reality of my life and imperial citizenship at the center of a global power structure. At the Mexican Consulate, the Nicaraguan got a one-month visa, the Russian got a three-month visa, and the American without even a passport got a six-month visa. And then there are the mirror "Check Point Charlies": one sixty miles north of the border past Oceanside, surrounded by a massive US military base, tanks and helicopters always raising dust to the right and left; and the other sixty or so miles south, right past Ensenada. The scenery is beautiful, but it can't sufficiently hide naked geopolitical realities.

The difference between the mirror Check Point Charlies is the difference between clean cut, smartly uniformed if slightly sinister INS officers on the American side and, on the Mexican side, lounging, unshaven, generally brutal and brutalized kids in full fatigues, sporting heavy caliber automatic weapons. It's the difference between an empire, America, that masks from its own citizens the naked power it musters to use against peoples elsewhere around the world, and a imperial colony, such as Mexico effectively is, in which military might serves only one real purpose, the pacification of the domestic population.

As a Nicaraguan citizen in exile, Lucio stiffened at the wheel every time we passed a convoy of trucks and armored vehicles. And we passed them often. I couldn't help thinking of Chiapas, and feeling unexpectedly Cuban. Margarita was indifferent. She grew up in Russia and came to America before the fall of the communist state. Daughter of an auto mechanic and a cafeteria worker, a genuine and genuinely spoilt "proletarian," she's the kind of Russian now nostalgic for the Breshnev years and, therefore, completely at ease with a military serving both internal and external imperial functions.

In truth, Lucio and I probably envied her unshakable equilibrium, her seemingly innate, survivalist assumption that all politics is irredeemable bullshit and, at worst, a petty annoyance to the real business of life. Nothing will ever change. "Let's go...."

In truth, Lucio and I probably envied her unshakable equilibrium, her seemingly innate, survivalist assumption that all politics is irredeemable bullshit and, at worst, a petty annoyance to the real business of life. Nothing will ever change. "Let's go...."

In San Quintin, the real business of life was sunning, clamming, fishing, eating, and, of course, photographing Rita doing all of the above before she turns eighty the day after tomorrow. Accidental tourists, we stumbled onto the clamming. We didn't know, but the beaches there are quite famous for them. All the local restaurants serve them, but the best are to be had from the roadside stands set up for nothing but that purpose. If you make the mistake of stopping, you end up staying for an hour, asking the guys who work the stands to split just another and another and another. And they laugh all along, because once you've stopped, they've got you hooked.

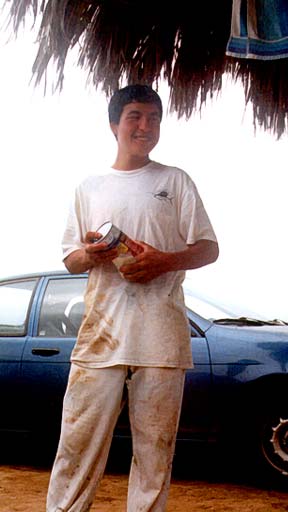

It was David who told us about the clams, or rather showed us, showed Margarita first, because he's only starting to learn English and, though pronouncing perfectly what little he did know, proved to be quite shy about it. David was the 19-year old chef at the local resort-campground where we stayed. A first-rate cook and a charming, impossibly nice kid, he's not a local. Like so many other Mexicans in Baja, he's there from elsewhere for the work, for the boom times that have come with development for American tourists and expatriates. David's on a career path. He's broadening his menu and his English. He's good enough at both, at 19, that he'll work his way through the Mexican resorts along the Baja coast, moving always north. Someday, if things go his way, he'll be cooking Italian, French, or hybrid California cuisine in some up-scale restaurant in San Diego, LA, the San Francisco Bay Area. He's shy now, but it's easy to see that he's got the talent and focus to get there.

Or at least it's nice to think so. There's no life path that isn't really a long series of unexpected detours to outcomes one never could have anticipated.

Or at least it's nice to think so. There's no life path that isn't really a long series of unexpected detours to outcomes one never could have anticipated.

In any event, David adopted us, as he no doubt adopts any group of Americans who prove friendly and unpretentious, for the English he could pick up and for news about food and cooking in America. Lucio was a great catch, in this respect, not only speaking English and Spanish but also having spent a good many years as a waiter in top-flight Italian restaurants. And we, as pathetic and disorganized car campers, were definitely in the unpretentious class. As a result, we ate very well. David brought a bit of the best of each night's menu for us, or rather for Lucio to try, and in the end he was pleased to walk away with a can of Campbell's (How awful is it?) and a can of tuna, with advice on how to read the English label for "solid white, in water."

In addition to clamming, we tried fishing, or rather Lucio tried. Margarita and I had no dreams of the perfect Baja beach existence to drive us on, so we stuck to watching. But Lucio waded right in, at least as far as his always lit cigarette would let him go. Actually, that was where we first met David, not at the resort. We found him down in the waves, the first afternoon we were there. He saw Margarita excited by the tiny clams she was finding washed up by the surf, and dug down to show her how big they really were if you were willing to get totally sopped. Lucio came along and saw David's fishing gear: a line, with regular weights and hooks, wrapped around a makeshift beer-bottle casting reel. It reminded him of similar wooden spool ones he had used in Nicaragua, but improved by the slickness of the bottle, which allowed the line to fly off more freely. So the next day we were back, together on the beach, with a fresh set of weights and hooks Lucio bought for himself and David, and bottle spools David provided, lines cut to the right length and already wrapped.

The basic trick of fishing with this gear is simple enough, although it requires a bit of practice to get it right. You have to whirl the baited and weighted end of the line over your head with one hand, and then release it at just the right moment so that it sails as far as possible out to sea, pulling the line off the butt end of the beer bottle, grasped by the neck in your other hand. There's also a timing issue with the bottle, which must be pointed up and seaward at just the right angle for the moment so as not to drag the sailing line back in mid flight. Then you wait. Then you reel in, wrapping the line around the bottle to start again. Of course, since it's true Fishing by any name, there's endless room for fruitless speculation and mythologizing about the ideal number and size of weights and hooks, and their distribution on the end of the line. And then there's the issue of bait, in this case a choice between old fish from the resort kitchen or bits of clam fresh from the beach.

For two consecutive days, they got very, very wet, and caught absolutely nothing. But it was "good fishing" nonetheless. We ate the clam bait.

For two consecutive days, they got very, very wet, and caught absolutely nothing. But it was "good fishing" nonetheless. We ate the clam bait.

It was all like that. Everything that happened, happened fortuitously. We planned nothing, except how to get there, and even that we didn't do very well. It took us four hours just to clear Tijuana, because we wandered around in circles, through the peripheral American-style shopping malls that have sprung up outside the center of town, looking for a bank authorized to take our token visa-travel payments and stamp our papers. It was a new scheme to grab a few more dollars from border-crossing adventurers, and most of the banks hadn't the slightest idea they were on any list or why. But the tellers were all very amused by it, by the scheme, and we would never have met them nor negotiated so many truly devious mall parking lot mazes, but for the new travel requirements.

If you want to see what American mall parking lots would look like if developers here dared, just take a ramble through Tijuana's mall lots. You can get in, but just try getting out, before or after you've paid for the privilege.

In any event, everything was fortuitous. We eventually arrived at our campground and, aside from trips to town to buy food and look around, we never left. Everything, everyone, and every creature came to us. Preceding David, the first night we were discovered by the resort's watch dog. An old, bedraggled beast, he was very polite and very cautious about approaching us. We had sympathy until we found out why, when he snagged two sandwiches right out of the trunk of our car the moment our backs were turned. He did give them up, when confronted. But he probably also knew from experience that by then it was too late, that we'd likely hand them right back rather than eat them ourselves. Which we did, and firmly established that as the basis of our relationship for the duration of our stay.

After that first night, the word apparently got out, and all the resort's residents made their way over to our campsite, except the goats because they were chained up. The most spectacular, were the two peacocks.

They ate just about anything and competed with Margarita for photo-ops. We were also visited by a mismatched pair of puppies, brought by David and the resort owner's ten-year old granddaughter. She came on a bicycle with training wheels, speaking perfect English and Spanish, with lots of questions. We concluded she was a self-appointed spy: her mission to learn everything she could about us and about what David was doing hanging out with us. She immediately preceded our most imposing and intimidating visitor, "Porky," a large, old, and not easily moved or removed Vietnamese pig, with two huge tusk teeth.

As Porky slowly approached a hue and cry of contradictory warnings marked his progress. Don't feed him! Don't NOT feed him! Make him go back! Don't stand in his way! Apparently, Porky, in his old age, had become very cantankerous, easily angered and easily offended by anything that even hinted at an impediment to his moment by moment desires. (Somehow he made me think with dread about what Margarita will be like at 80, when she finally starts to look at those photo albums.) Fortunately Porky had one great weakness: grapes. Threats and prods with a baseball bat had no effect, but he could be moved anywhere by leading the way and repeating, "Porky. Porky. Grapes. Grapes, Porky. Grapes!" After half an hour of that things settled back to normal and we could enjoy what food we had left.

Our last visitors arrived the afternoon we left, after a brief morning downpour, which had been threatening for days and had been responsible, according to the locals, for the extraordinary number of flies about during that time. Seems there was some truth in that. At least, when the storm finally came, the flies all magically disappeared. The rain was beautiful, raising little clouds of dust everywhere the enormous raindrops exploded upon the otherwise dry, cracked dirt. Margarita and Lucio took shelter in the tent, but I sat outside, under our campsite cabana, as the storm blew through. Afterward came our last visitors: hundreds of "stink beetles," as I grew up calling them, which appeared out of the same nowhere into which the flies had vanished, the moment the rain had stopped.

It's a pleasure to discover, once again, that nature's movements are still vast, indifferent to technology, capable of driving man, beast, and all other species before them. And on that note, we packed up and drove off into the not-so proverbial sunset.